Keris: The Sacred Daggers of Indonesia

A keris is a double-edged asymmetrical dagger originating in Java. It is both a weapon and a ritual object loaded with spiritual significance.

Keris are also indigenous to Malaysia, Thailand, Brunei, Singapore and the Philippines where it is known as kalis, with sword variants.

The keris is widely distributed throughout the areas of influence of the Majapahit Empire, and in the Cham areas of Cambodia, who are heirs to the ancient Shiva-Buddha religion that once spanned all of Southeast Asia. It also appeared in the Dong-Son culture of Vietnam as early as 300 B.C.

Keris have been forged from iron by master craftsmen for hundreds of years. Creation of the daggers involved complex rituals to boost their connection with the spirit world and put magic power into the hands of those who carried them.

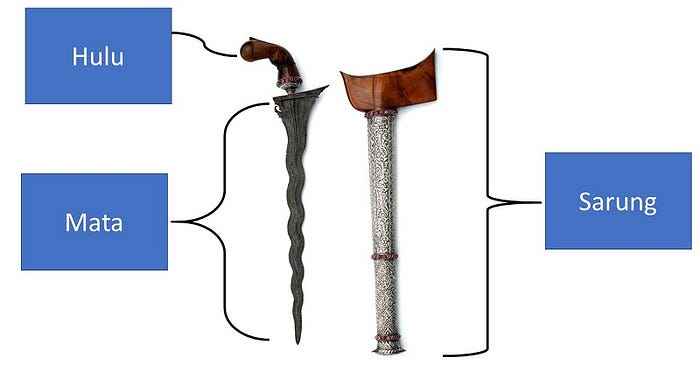

Structure of the Keris

The Keris is a complex piece of art, with each detail having significant meanings and serving specific magical and spiritual purposes.

The blade of the keris, the hilt and also the scabbard all present their own iconography.

However, these last two elements are seen as subject to changes. Only the blade remains a constant, and only the blade is regarded as having a spiritual element.

Keris blades have two kinds of shape: straight and meandering. There are approximately 200 kinds of straight keris and 250 kinds of meandering keris. The older types of keris from before the Majapahit era have straight blades.

• The hilt (hulu) is often carved in meticulous details and made from various materials: precious woods, gold or ivory. They often show animal figures, spiritual beings and deities, although this became less common with the introduction of Islam, especially in Malaysia.

• The blade’s surface usually bears a pattern called pamor, which is produced during the forging process, and made visible by etching. Pamor patterns have specific meanings and names which indicate the mythical properties they are believed to impart. There are around 60 recognized pamor variants.

• The number of curves (luk) on the blade is always odd, from luk 3 up to luk 13. (in reality, from 1 to 11 as will be explained below)

• Dhapur is the general shape or outline: straight (lurus) or wavy (luk). The number of waves is always odd, but sometimes difficult to distinguish the last odd curve.

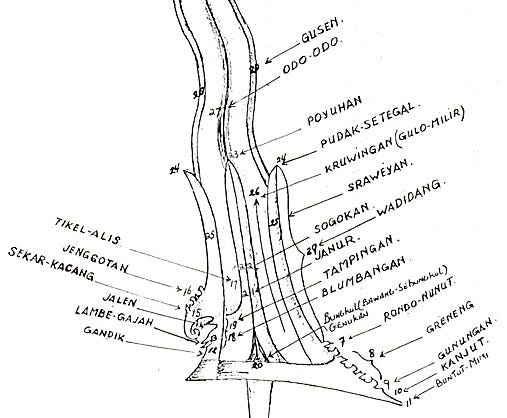

• Perabot are the sculptured or chiseled features found at the bottom half of the blade. Ina well-made keris, these features are considerably intricate.

• Kinatah are the gold encrustations showing carvings of various spiritual beings such as Nagas.

• Mendak (or Selut) is the decorative metal ring that is between the hilt and blade They are always made of metal — brass, silver, copper, gold mixed with copper and sometimes set with plain faceted gemstone.

Features (ricikan) of the keris

Magical Powers of the Keris

Some keris are considered to possess magical powers, with some blades possessing either good or bad luck. Some legendary keris that possess supernatural powers were mentioned in Indonesian folktales, such as those of Empu Gandring, Taming Sari and Setan Kober.

Some keris are forged entirely for magic and spiritual purposes. The creation is a complicated magical ritual which involves the blending of the metal with magical ingredients and the invoking of powerful hyang (spirits) into the keris.

After keris has been created, the spirit is continuously fed in order to make it more powerful. Keris should be hung on the wall and fed once a month. They will work quietly behind you, protecting you from harm, or drawing in wealth and good luck.

Some keris are more suitable for experienced magicians, and some are easier to be used by beginners. Others were created as protector keris, and can be used with no magical knowledge at all. There are some that can be carried on the person to confer authority on the carrier.

Ritual forging process by master empu (blacksmiths)

A properly empowered keris can bring good tidings or disastrous luck, depending upon the empu’s intention while the blade is forged. The empu typically recites a mantra over steel while meditating for inspiration and divine guidance before crafting a keris. Other elements that are said to make a keris more powerful:

• It should be of a respectable age (the older, the better).

• Its dhapur (style) and pamor (mix of metals) should complement the owner’s personality.

• If it contains meteoric metals, it is considered more powerful. Blending of metals from the earth and sky are supposed to result in a particularly powerful weapon.

The keris is designed in accordance with the ancient principles of the Sathapatha Brahmana. True keris were forged in layers of various irons and nickel that were folded together repeatedly. Some blades were folded hundreds of times and took years to finish, just like Japanese samurai swords.

A keris made according to the traditional methods can take up to almost one year. However, modern ones manufactured with modern machinery take only 1 to 2 weeks.

To test a blade, the owner is advised to sleep with the Keris under his pillow. Depending on whether his dream are good or bad, he would then know if the blade is right for him.

Owners of true Keris are required to conduct special ceremonies to retain the weapon’s powers. They have to wash the keris on the first Javanese lunar year with offerings consisting of flowers and incense. Neglect of the keris may cause the guardian spirit to depart, leaving the keris powerless.

The luk (waves) count of the keris

The original keris, the Keris Buda, had only the straight form. With the emergence of the modern Keris before the Majapahit era, waved blades appeared.

In Majapahit society, as in today’s Balinese society, one indicator of status was and is the tiered roof (both as a shrine in a temple complex where the number of tiers in the roof indicates the status of the deity to whom it is dedicated, and as a cremation tower or bade where the number of tiers in the roof indicates the status of the person being cremated).

Tiered roof in shrines represent Mount Meru, the dwelling place of the gods. The tiered roofs must always be an odd number of tiers: 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, with the highest number of tiers only able to be used on the roof of a shrine dedicated to the Supreme God, Shiva.

The number of waves in a keris blade must also be an odd number. However the maximum number of waves in the blade of a keris is said to be 13 — two more waves than are permitted in the roof of a meru shrine.

The explanation is given by A. G. Maisey in ‘An Interpretation of the Pre-Islamic Javanese Keris‘:

“The final wave simply does not exist, it is the straight section of the blade at its point, but to achieve an odd number, an imaginary wave is added. Similarly, the first wave counted is not a wave in the blade either; it is a slight undulation that occurs on only one side of the blade.

To make a long story short:

“This convention of counting waves is based upon a fallacy — The blade wave that is currently counted as the first wave is in fact not a wave in the blade at all. The first true wave in a blade occurs with the first convex wave above the gandhik, or the first concave wave above the wadidang.”

“When the wave count acknowledges the actual waves forged into the blade by its maker rather than adding two imaginary waves to the number of waves created by the maker, the number of waves counted is two less than when the count is conducted according to the current convention.

Using this method of counting waves the highest number of waves found in a normal keris blade becomes 11, not 13, and this aligns exactly to the highest number of waves to be found in a meru.”

Threfore, the shrine and the cremation tower are representations of Mt. Meru, and the keris is also a symbolic representation of Mt. Meru.

The roof of the shrine and of the cremation tower can have a maximum of only 11 tiers, thus the normal keris can also have only 11 luk, corresponding to the 11 roof tiers.

There is no problem in achieving this count of one luk to 11 luk; all that is necessary is to count the actual waves in a blade and ignore the convention that demands two non-existent waves be added to the count.

When the Javanese keris had to adapt to the islamic culture, some elements of its iconography needed to be altered to make it acceptable to the Mohammedan faith.

Because the highest number of waves permitted in a keris blade was 11, this being the number to which only the highest deities or a king was entitled as a status indicator.

The number 11 is the highest number permissible as an indicator of the status for gods, and for men in Indonesian Hinduism, just as the number of tiers in the roof of his cremation tower were indicative of his status.

The Moslems then decreed that the wave count in a blade should ignore the first true blade wave and commence at the first slight undulation in the blade, rather than the first complete wave.

This resulted in a count of waves that was two more than had previously been the case. With this, the Moslems sought to destroy the spiritual significance of the keris and its relation with social status as it was in the Majapahit society.

Under the current, Moslem-Javanese convention of keris count, the lowest number of waves a blade can have is three, so all blades fall within the range of 3 to 13 waves. There is no one wave keris, and any keris of more than 13 waves is considered to be unusual.

However, within the real system of counting, there is a place for a single meru roof, and there can be no more roof tiers than eleven. By applying the wave count properly therefore, we are able to produce a keris wave count of 1 wave to 11 waves, and a keris that has no waves: the straight keris.

Keris Buda

Prior to 1300, the keris was in the form now known as the Keris Buda, a short straight dagger , leaf-shaped and with a splayed base. Such kerises are depicted in the reliefs of Borobudur or in the Shiva temple complex at Prambanan.

The Keris Buda have a leaf-shaped blade resembling the Gunungan, or Cosmic Mountain, which has huge spiritual implications.

The triangular form of the Keris Buda can be understood as both a representation of Shiva (Siwa in Javanese), and also as an almost perfect representation of the Javanese Gunungan.

The Gunungan form of the Keris Buda associate it with Mount Meru and with the Tree of Life.

The strong central rib in these dagger forms represents the trunk of the Kalpataru, or Kalpavriksha tree, which is a symbolic passageway from the natural world to the supernatural world, or from the seen to the unseen world (sekala and niskala).

When the keris is interpreted as the Gunungan, it is also interpreted as a representation of Mount Meru, and thus as symbolic of Shiva. The sogokan part is said to represent the lingga and the blumbangan part, the yoni.

The modern Keris

By 1437 the modern Keris had appeared, as shown on reliefs at Candi Sukuh. Most keris buda do not carry pamor, while modern keris have pamor. Keris with pamor appeared in East Java during the three hundred years between 1000–1300 A.D.

Candi Sukuh and Candi Panataran seem to have been master temples where forging of keris and their spiritual and magical consecration occured. This is where their modern form and style of the sophisticated modern keris was refined and solidified.

The development of the modern keris happened by losing the heavy pommel and refining the blade form of the daggers, which allowed to wear the dagger more conveniently in the daily life.

As the pommel disappeared and the blade became lighter, the weapon became more easy to carry, dissimulate and more suitable for rapid fighting.

The waved form of blade made it possible to create as much damage to an opponent as the larger blade of the keris buda would have done, but with a much lighter blade. The waving of the blade also allows it to be more easily withdrawn from a wound.

The sogokan, kembang kacang and greneng are features that help to divert blood from the grip.

The political unrest of the period is a possible factor in the development of the modern keris from the keris buda. In such times a light, fast, thrusting weapon would tend to be more useful than a weapon used with a slower overarm stabbing action.

Particularly so if the social environment was unsettled, and it was considered desirable to always have a means of defense at hand.

Image source: pusakadunia.com

The Ganapatyas and the formation of the modern Keris

Most of the features to be found in the modern Keris are difficult or even impossible to explain in functional terms. They serve spiritual purposes only.

The features of the modern keris that were developed during the Majapahit era, and that did not exist prior to this are: kembang kacang, lambe gajah, jalen, greneng with ron dha, luk and the icons.

The kembang kacang (“bean flower”) appears in company with the lambe gajah (Elephant’s Lip) and the jalen (a small, sharp, sacred grass. The kembang kacang represents the elephant’s trunk, with the lambe gajah as lip and the jalen as tusk.

Those are forms clearly associated with Ganesha and have been introduced by the well-established Ganapatya spiritual lineage in Java.

Gajahmada was a member of the Ganapatya denomination of the Shiva-Buddha religion. For instance, the Ganesha pratima (statue) in Candi Singasari is a deification of Gajahmada as Ganesha.

The worship of Ganesha is regarded as a part of the worship of other deities. Most Hindus commence their prayers with a prayer to Ganesha.

Ganesha is one of the panca-devata (five major deities) and the worship of Ganesha has formed a part of the worship of Shiva since at least the 5th century.

In Java, Ganesha is revered as the Remover of Obstacles, the God of Knowledge and Education, the God to whom one prayed for success and he was prayed to before the beginning of any new undertaking.

In court circles before the 16th century, Ganesha was revered as a military leader and destroyer of enemies, which is why Gajahmada added Gajah to his name.

The modern keris is therefore a product of the Shaivist Ganapatya cult of the Majapahit empire. The keris is like a “frozen mantra” addressed to Shiva and Ganesha, which is very fitting for a kingdom that was attempting to strengthen and broaden its power base.

Two types of Keris Ganesha

The Ron Dha

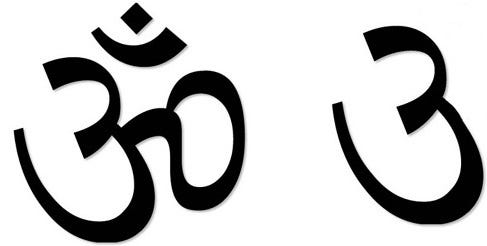

The Ron Dha feature which is part of the greneng, is today explained as a representation of the Javanese letter dha.

Javanese Moslems of course try to explain that the Ron Dha is a representation of the name “Allah”. However, the Ron Dha already existed in the pre-Islamic keris, and exists in the Balinese keris as well.

The letter dha in Javanese scripts corresponds to the number 8. In the Candra Sangkala numerological system, 8 is the numerological value of both the Nagas and of the Elephant. Knowing the association of the keris with both the Nagas and the Elephant, this is one probable reason.

The original reason however is that the Ron Dha is a simplified way of writing the supreme mantra “OM”, depending upon the script used, and the purpose for which it is written.

Indeed, when the mantra “OM” is written for religious purposes, it is not written as the complete word, but rather it is written as a symbol that is only part of the complete word.

In the Balinese script (that is descended from the Kawi script used in Majapahit), the major part of the letter “OM” is a clear representation of the early form of the Ron Dha. The symbol now euphemistically referred to as the “Ron Dha” is a therefore the physical representation of the sacred mantra OM.

Figures on the Keris

In the best keris, various figures are carved into the metal, usually found in the wider sorsoran area of the blade. They most often include representations of the Naga, of the Singo Barong, and of Bhoma.

• Naga — The keris is symbolic of Shiva, the Gunungan and of Mt. Meru. Once this is understood, there is no mystery about the Naga. In the Asian myths, Vishnu used Mt. Meru as the churning stick to churn the Great Milk Ocean, and he used the Naga Vasuki (Javanese: Basuki) as the churning rope.

The keris itself is a representation of the Gunungan (Mount Meru, which is an icon of Shiva). The Naga Basuki was used as the churning rope to hold Mt. Meru, and was later worn by Shiva as a sash. The Naga motif when it appears on the keris is a representation of the Naga Basuki.

The Naga Basuki is a binding force, and the function of the Pusaka Keris is to bind all within the group to which the Pusaka Keris relates. When the Naga Basuki appears on a keris this reinforces the cultural position of the keris as an icon of society that unites all members of the society.

Keris Naga Raja Luk 9 (left), Keris Naga Sasra Luk 13 (right)

• Singo Barong — There seems to be some evidence that the Singo Barong, a representation of a lion, was a symbol associated with high ranking Ksatriya nobles. This is indicated by the sarcophagi which were the prerogative of high ranking nobles, members of the Ksatriya Caste, in olden times in Bali. These nobles had the right to a sarcophagus in the form of a winged lion

The Singo Barong is not winged, but in Hindu tradition, the lion is associated with the warrior caste. Possibly the wings on a sarcophagus lion were added because of the implication of the spirit of the deceased flying upwards from the cremation.

Keris Singa Barong

- Bhoma — Bhoma (or Kala in Java), is said to be the child of water and earth, which results in the growth of plants, which equates to prosperity. In Sanscrit, Bhoma means “born of the earth”. When Bhoma appears in the base of the keris blade this is a reinforcement of the Mt. Meru representation, as the lower slopes of Mt. Meru are covered in foliage, and this is the abode of Bhoma. But Bhoma is also a protective deity, so the inclusion of Bhoma in a keris also provides protection from evil.

Keris Garuda (left), Keris Rakasha (right)

After the islamization of Java, the Javanese empu (master keris makers) had to progressively dissimulate many of their features to conform with the Moslem ideology that prohibits the depictions of spiritual beings.

The luk waves lost their meaning, the mantra OM (ron dha) became an icon of “Allah”, and the symbols of Shiva (the sogokan) and Ganesha (the kembang kacang), became merely ornaments with no meaning.

The erosion and final collapse of the Majapahit empire resulted in the influx of nobles and artisans into Bali. They brought their knowledge with them.

As a result, the Balinese keris are still made according to the original knowledge.

Washing the Keris (Ritual Cleansing)

In Java, the Keris cleansing is a made during the holy month of Suro. It is part of a series of purification rituals which include the Siraman Pusaka (heirlooms cleansing).

To etch the blade you need the following ingredients:

• lime, lemon or concentrated citric acid

• sour coconut juice or a mild detergent

• water

• a brush / a tooth brush

• a container, which fits the length of the blade

• raw orange arsenic: Realgar, or arsenic trioxide

1. Mutih, to clean the blade:

• The hilt is removed from the blade

• To remove the oil, soak the blade into sour coconut juice and brush it with a solution of klerak (Sapindus rarak DC), a local fruit. A mild detergent with warm water is also efficient but less exotic. If it is protected with wax, ethanol will be more appropriate.

• To remove the old arsenic and the rust, soak the blade into a solution of lime juice until the blade is white and shiny. For those who do not have limes, a solution of denatured alcohol with 10% citric acid will do the job.

• Remove the blade once a day and scrub it under running water with a tooth brush to remove the lime solution. When it is clean, dry it in the open in the sun, or with a hair drier. Most blades will come clear in a week, some might take longer.

2. Marangi, to etch the blade. There are two processes:

By immersion:

• Take a piece of warangan (raw orange arsenic, Realgar), pound it until it becomes powder. Mix one tea spoon of this arsenic powder in 1 liter solution of fresh lime and water.

• Soak the blade in the solution. Blades react differently, some may show a very nice pattern in a few minutes, others will take hours or days. If the blade has been soaked for several hours in the arsenic bath, it might be necessary to rinse it with a lime solution to remove the excess of arsenic.

By application:

• Mix the arsenic powder (or liquid) with a few drops of lime, progressively add more lime to produce a solution to fill a third of an egg cup. Let the solution sit for 30 min.

• Damp a soft brush in the solution and then rub the brush on the blade. Repeat until the blade darkens. Once you get the color you want, rinse under running water. Older blades will tend to be more gray rather than black.

• To prevent further rusting, the blade is dried in the sun or with a hairdryer.

3. Anjamasi, to protect the blade:

• Coat with a brush a thin layer of minyak or micro crystalline wax. Minyak is a mixture of several kind of oils, often based on sandalwood oil, to flagrant and protect the blade. The blade is then dried in the open air.

• The warangan solution can be kept several years, you just need to add warangan each time you use it. In fact, like good wine, it improves with time

Keris Glossary of Terms

• Alas — Alasan pattern -Forest pattern.

• Baja — Steel

• Blewah — A pendok with an open front.

• Brojol — A straight keris form bearing only a blumbangan.

• Buntut — The swelling sometimes found at the end of the gandar.

• Cecekan — The small areas of carving (normally 2) on a Central Javanese planar ukiran which are said to be the stylised representation of a kala face.

• Dhapur — The form of a keris

• Godean — A village near Jogjakarta which has made keris and other wesi aji since the time of the second kingdom of Mataram.

• Gonjo Iras — Literally:-two things combined into one.A keris blade with the gonjo forged into the blade.

• Gunungan — The mountain figure used by a dalang to open a wayang play. It is a symbol of the universe.

• Gusen- or kusen — a border or frame; in a keris, the edge bevel, framing the body of the blade.

• Ilat-ilatan — literally a “tongue”, it is the thin piece of metal used to back the krawangan face of an open-work pendok.

• Kemalo — Enamel

• Kendit — Belt.

• Kinatah — Decorative gold work applied to a blade.

• Landean — the shaft of a tombak.

• Lis -A collar found on some pendok.

• Mamas — A nickel alloy, similar to nickel silver.

• Mendak — Small ring fitted below handle.

• Metuk — A small round, shaped ballaster at the base of a tombak blade which forms the transition from blade to shaft

• Naga — The mythical dragon of all Asian cultures.

• Nguceng mati — The gonjo form that has a sharp pointed buntut urang.

• Pamor — The pattern produced in a blade by pattern welding,etching ,staining.

• Pawakan — the overall visual impression of a keris blade.

• Pedang — A sword. Pedang Sabet is a slashing sword. Pedang Suduk is a stabbing sword.

• Pendok — Metal cover for lower part of scabbard.

• Polos — Unadorned.

• Raksasa — Mythical demon.

• Ricikan — The features of a keris blade.

• Ron Duru — Leaf of the duru tree. Properly ron genduru.

• Raja Gundala (or ‘gundolorojo’) — A pamor motif with various forms, all being able to be interpreted as a human-like or animal-like form; talismanically this pamor can protect against black magic and torment by ghosts or spirits.

• Sanak — Related. Pamor or iron which achieves its effect thru weld joints rather than high contrast. We would call damascus steel “sanak”.

• Sebit rontal — (sebet rontal, nyebit rontal) the gonjo form that has a wide buntut urang and curved sides.

• Selut — A cup, usually metal, which encloses the base of the handle, and sits on the mendak.

• Singo Barong — A lion-dog. Similar in appearance to the lion-dogs which guard Chinese temples.

• Sirah Sawer — sirah=snake (high Javanese), sirah= name of pommel end of Javanese keris hilt, thus broadly”hilt with snake at pommel”.

• Slorokan — A type of pendok fitted with a “slorok”, or “drawer”, i.e. a sliding front panel.

• Sorsoran — The base of a keris blade, to the point (poyuhan) of the sogokan.

• Suasa — Rose gold, usually of low gold content, can also be applied to pinchbeck, which is an alloy of copper and zinc

• Tangguh — The Javanese system of blade classification which uses stylistic and material characteristics to place a blade in a historical or geographic context.

• Tangkis — A means of warding off, or a shield; a blade is said to have pamor tangkis when it carries a different pamor motif on each of its blade faces, and this is considered to be a talisman against black magic.

• Templek — When applied to a pendok it denotes a construction utilising a fretwork panel affixed to the front of the pendok. Normally the highest quality pendok style.

• Timoho — A wood of mottled yellow and brown appearance, which is one of the most highly regarded traditional woods for wrongkos,now virtually extinct.

• Trembalu — A highly esteemed wood used for wrongkos, now virtually extinct, and characterised by its chatoyant grain.

• Ukiran — Keris handle.

• Wlagri — the metal ring that is sometimes fitted along with a godi.

• Wos Wutah — Scattered rice grains. The most common random pamor.

• Wrongko — Scabbard.