Gāyatrī Rajapatni: Uncovering the Woman Behind Majapahit

Image source — Didi Trowulanesia

Originally posted on Indosphere.co

“The central figure was this statue and it just mesmerized me.” That is how Earl Drake, former Canadian ambassador to Indonesia, describes his discovery of Gāyatrī Rajapatni, a powerful and woman of the Majapahit kingdom.

Seven years after his encounter with that 14th-century feat of artistry at Washington, D.C.’s Freer Gallery, Drake describes a visit to a Tokyo museum. There she was again. “There was clearly a message here,” he says.

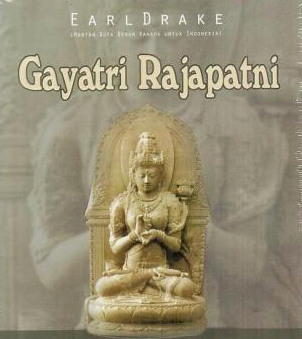

The result of those fateful meetings is a new book, Gayatri Rajapatni: The Woman Behind the Glory of Majapahit, about a woman so important that she figures centrally in a Majapahit epic poem, one of the few remaining records from that time.

Drake has used that work — the Nagarakertagama — as well as Chinese records, later texts like the Pararaton and various kidung (songs), and that stone statue of Gāyatrī to craft a story of the woman and her role in Majapahit affairs.

On the graceful figure he observed twice during its world travels, and which now sits in the National Museum in Jakarta, he says, “It’s just sublime … This is so special, it’s the first portrait sculpture in Indonesian art history … This is a real woman even though she’s holding attributes of a goddess, the quality of the stone is better, the workmanship is better. It just grabbed me and I thought this is the key to it. This person was so important that she got the most special statue in Indonesian history.”

The East Javanese statue of Prajnaparamita was probably the deified personification of Gayatri Rajapatni

Before beginning work in Canada’s foreign service, Drake was a history student. “I thought I wanted to be a history professor … my Ph.D. advisor advised me to get out and see the world and I’d be a better history professor, and so I’m now back to it after 50 years. So I was always a historian before I became a diplomat.”

After a career that includes diplomatic work in Karachi from 1956–58 and Kuala Lumpur from 1961–1964, and a position as an executive director of the World Bank from 1975–82, Drake has certainly seen the world, but has somehow returned to Indonesia. Currently Honorary Professor in Residence at the Institute of Asian Research at the University of British Columbia, Drake is clearly passionate about Indonesian history and Gāyatrī.

He says, “I was puzzled by Indonesia because of all the Asian countries I dealt with it was the country least known to the West, the most mysterious. And one of the things I used to do as a historian, whenever I’d go to a country I’d say ‘Well what is your golden age? What is the period you look back to that inspires you?’ I asked that question here and couldn’t get a clear answer. Several people said Majapahit, but then anybody from Sunda [West Java] said absolutely not, that was a terrible period … I thought it was a mystery here that there’s no consensus,” he says.

After retiring from Canada’s foreign service and other work in Asia, especially China, Drake immersed himself in this mystery of Indonesian history and Gāyatrī with the help of new translations of the Nagarakertagama and the Pararaton.

Prapanca completed the Nagarakertagama in 1365, and it includes these words in poetic Old Javanese:

“Now as for the renowned Rajapatni, she was the King’s maternal grandmother

Who was like an embodiment of the goddess Paramabhagawati, an excellent parasol for the world

Exerting herself in yoga, she practiced Buddhist meditation as a nun, venerable and shaven headed

In saka ‘sight-seven-suns’ [AD 1350] she was laid to rest, having passed away and gone to the realm of the Buddha

At the return of the illustrious Rajapatni to the Buddha’s abode, left behind the world was sad and bewildered.”

What Drake found in lines like these and others was a woman of the court who was powerful and educated, devout and political. “This is the central figure. She’s the missing person. She’s the one who holds it all together.

She was the daughter of Kertanegara, the king of Singasari, the martyred king…

She was the wife of Wijaya. She was the mother of Tribuwana who became the queen.

She was the grandmother of Hayam Wuruk. And I think she was the tutor of Gajah Mada.

She’s the one who pulls it all together.”

When asked if he found it significant that behind Majapahit’s glory was a woman, Drake said of certain women in history, “I think they haven’t been given adequate recognition. I mean I think they have always played that role but what happened here was that this woman was recognized in her time but because she never took the formal title of ruler her name doesn’t go down in the history books. So it’s been lost and I think it’s time it was restored.

And I think one of the reasons why she was so exceptional … was her father was the best educated king in the region and she was the best educated woman in the region. He made a point of educating her and so when you have a strong personality and you have a critical situation and an educated, dedicated woman it makes a difference.

And therefore, I think although [women’s roles in history] have always been important it’s important that every once in a while their role be highlighted and dramatized so people can understand that.”

He adds that he thinks Gāyatrī would make a wonderful role model for modern-day women, citing Kartini as one of the few women in Indonesian history still recognized and looked up to. […]

Asked what is next for him, he tells of meeting a young graduate student at Airlangga University in Surabaya and discussing a temple noted in the Nagarakertagama as erected in honor of Gāyatrī after her death (and perhaps the place where she was buried).

The temple sits somewhere, still undiscovered, in Majapahit territory in East Java in what was described as a grove of tamarind trees. Drake speaks of endeavoring to search for that temple, ever aiming to discover more about a woman who is no longer lost to history.

Via: Jakarta Post